Episode 3: BYG Records, an adventurous label, released a series of albums in the autumn of 1969 which became legendary when they invited the cream of American free jazz back from the Pan-African Festival in Algiers. A historic moment.

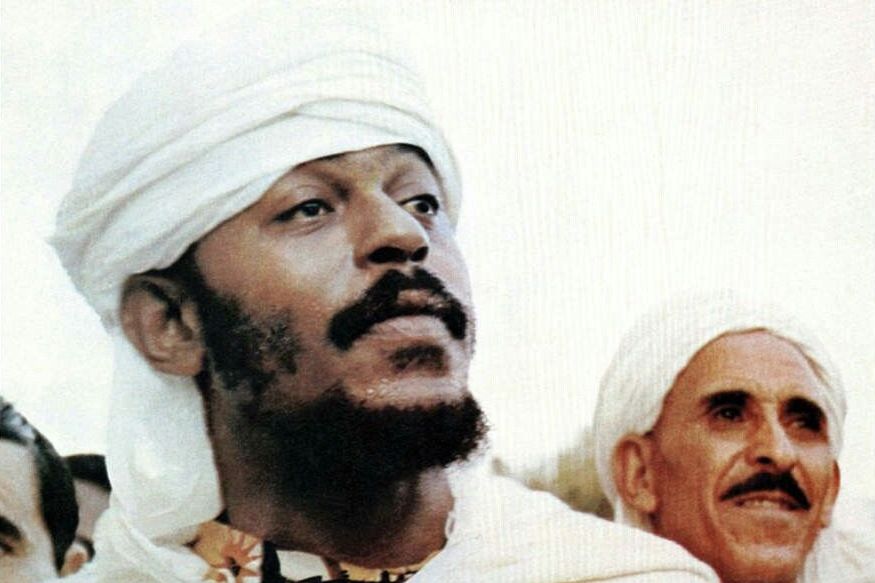

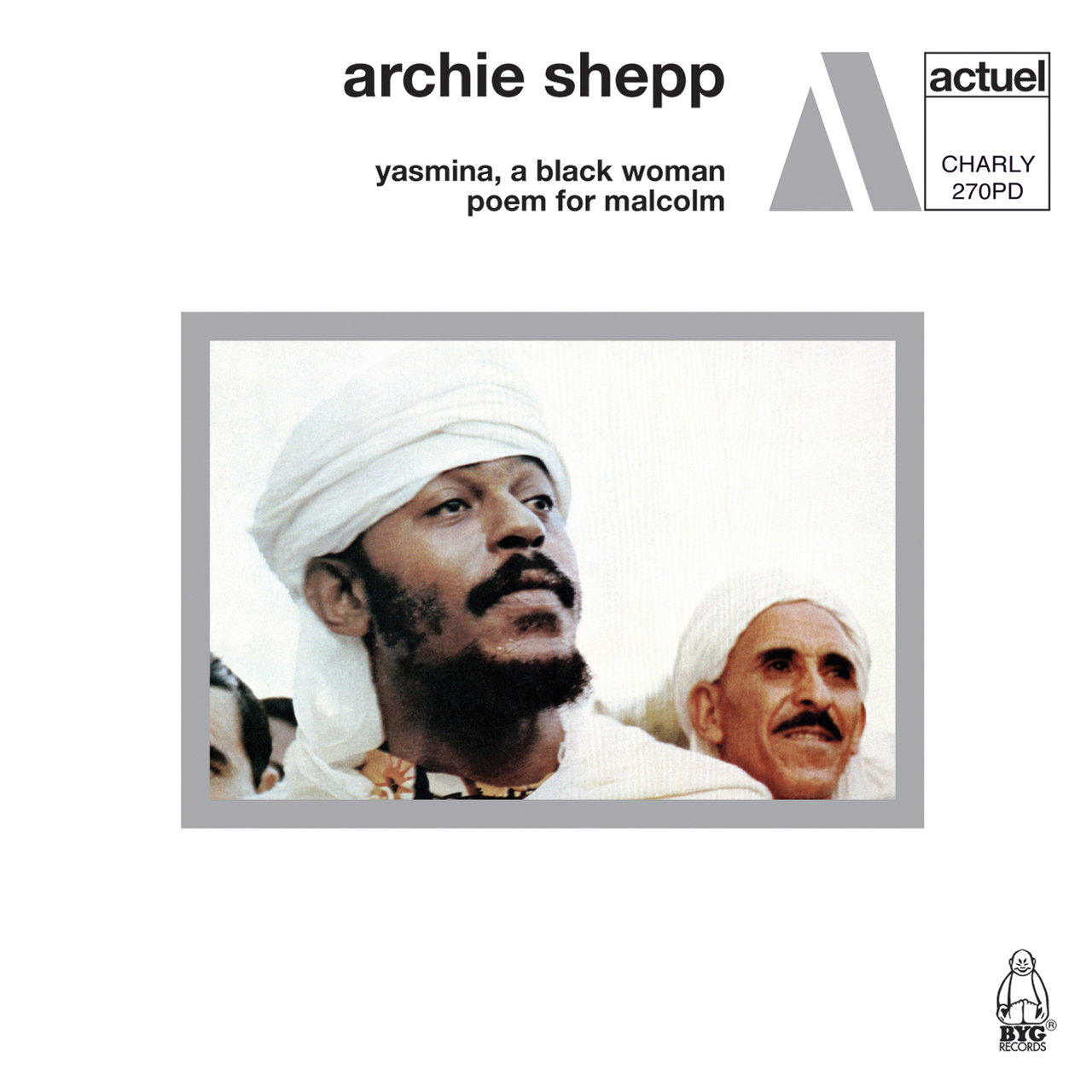

Photo: cover of Yasmina ,A Black Woman by Archie Shepp

August 1969, was Paris burning?

Our story begins when a band of jazz musicians has just disembarked from Algiers to record a series of albums that would become legendary: BYG! The label chose this acronym as its name, using the initials of their three founding fathers (Fernand) Boruso, (Jean-Luc) Young and Jean Georgakarakos, better known as Karakos.

It all started in the spring by the Champs- Élysées. “ Our offices were on Avenue de Friedland, and we regularly saw the soon-to-be big producer Philippe Constantin for coffee when he was working on Rue Lord Byron. We were two rival but friendly bands. I found out he wanted to start a free jazz label for EMI. We were on the same wavelength… ” remembered Karakos with a smile in 2014. In order to achieve this, he got backing from Claude Delcloo, a French drummer connected with the African American scene, and Jacques Bisceglia, a young jazz photographer. The first – editor-in-chief of the avant-garde music magazine Actuel – asked the second – who was leaving for the Pan-African festival in Algiers at the end of July – to recruit musicians and bring them back to Paris.

Archie Shepp © Guy Le Querrec / Magnum

Algiers, ‘Mecca for revolutionaries’

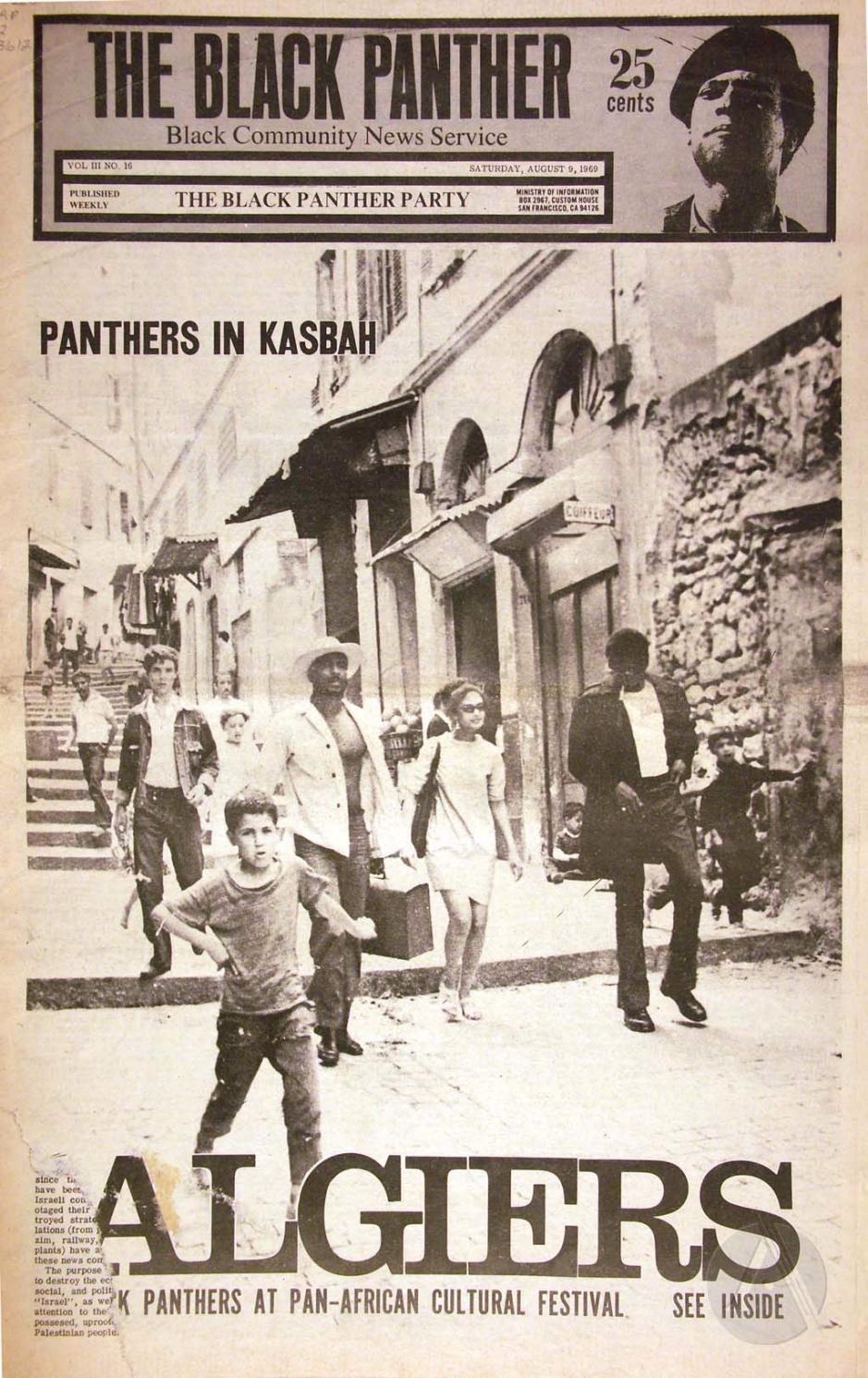

It was July 1969, and the city had become the capital of alternative movements. Summer on the other side of the Mediterranean promised to be a scorcher. The Black Panthers were spearheading their movement and had taken up residence in the white city, which had become ‘Mecca for revolutionaries’. In Algiers, where Eldridge Cleaver (the Black Panthers’ information minister who was wanted by the FBI and the CIA) had taken refuge, the Boumediène government, having seized power in a coup d’état four years earlier, planned to improve its image by organising a huge cultural festival, reflecting post-colonial politics. It would be the Pan-African Festival of Algiers, where many activists, from both sides of the Atlantic, would meet.

Intellectuals such as the Senegalese anthropologist Cheikh Anta Diop gave lectures alongside the great leaders of African liberation movements such as Amílcar Cabral and Agostinho Neto. There were African American civil rights poets like Maya Angelou and Ted Joans. Barry White, Nina Simone, and Manu Dibango were also there celebrating. But they weren’t the only ones in the overheating capital.

In 1969, South African Miriam Makeba, who had been banned from her country for ten years, had just married Black Panther leader Stokely Carmichael. Having become persona non grata in the United States, she would go on to compose “Do You Remember Malcolm”. Blacklisted and forced into exile once again, she found herself in Conakry, Guinea where President Ahmed Sékou Touré (the man who had said a firm ‘no’ to De Gaulle’s proposal that the country join a French community of nations, thus winning Guinea its independence) had become the focus of Black Pride on the continent and gave her a triumphant welcome. Makeba had the ear of an entire continent and was nicknamed ‘Mama Africa’. She remains an example for future generations fighting against segregation. The ‘Guinean’ Miriam Makeba was then made an Algerian citizen, and converted many young North African students to her cause. At the Atlas Hall at Bab El Oued, she sang “Ana Hourra fi El Djazaïr!” – I am free in Algeria! – in the presence of President Boumediène. With black glasses and dressed all in white, her presence made a lasting impression.

Photographer William Klein kept track of this performance in a documentary that has been described as a ‘Third World Opera’. The observer is immersed in the middle of the action, in the streets as well as in the cafés, on stage and backstage. The unfolding movement was on everybody’s lips and, for a summer, the idea of an African utopia was in the spotlight once more.

‘Jazz is African power’

Cal Massey, Oscar Peterson, Lester Bowie, Dave Burrell, Julio Finn, Malachi Flavors, Burton Greene, Philly Joe Jones, Jeanne Lee, Hank Mobley, Grachan Moncur III, Sunny Murray, Archie Shepp, Clifford Thortorn, Randy Weston…In Algiers, jazz was widely represented and duly celebrated, in all styles, though primarily through a free, open-minded style of jazz. The blues too, with Chicago Beau, as well as the gospel of Marion Williams. The joy and togetherness of an elated public felt really real during the happy reunion of the festival.

” The atmosphere was very warm and welcoming: each African country was represented, as well as the diaspora. It was beautiful. It was beautiful!’ recalled Archie Shepp forty years later. ‘Eldridge Cleaver, the Black Panther minister in exile in Algeria, invited me. I knew them but I wasn’t close to them. For us black Americans there was great excitement and pride in being there. We weren’t thinking in terms of North Africa, the Maghreb: it was more about the African continent. ”

Archie Shepp

In 1969, the saxophonist became aware of another reality, one more concrete than theoretical. The images of the gig he played with his growing quartet bear witness to this. Wearing a djellaba, Archie the post-Marxist kisses the ground, before coming on stage. ‘We’re black Americans, we’re Africans from the United States, we’re Africans first and foremost. We’re back. Jazz is black power, jazz is African power, jazz is African music.’ The message is clear. ‘From Chicago, From Alabama,’ a poet shouts as a group of Algerians clap their hands. From out of this melting pot cry Archie’s saxophone and Clifford Thorton’s cornet. ‘We’re back!’. In this crazy atmosphere the band of jazzmen take off, surrounded by whirling rhythms, tablahs and qalaqebs crash, zurna and zukra trace out spherical arabesques. It is an experience, a performance, all in a trance together. The two sides of the LP that will be released on BYG remind us that much during these performances was improvised and came from the heat of the moment. The drummer Sunny Murray – known for drumming in a manner as brilliant as it is wild and unexpected – was turned on his head by the earthy power of the percussion. ‘Brotherwood At Ketchaoua’ stresses another song. By the end of July, the atmosphere was one of brotherhood beyond words, despite the odd slight misunderstanding. It’s not always easy to agree.

The free waves of Algiers radiate over Paris

August 1969. Paris Orly airport. The final step on a great journey for most of the young free jazz lovers who’d filled up on music in Algiers. Jacques Bisceglia came to the Pan-African festival and took advantage of the occasion to make a date. See you in Paris? No! The party’s not quite over yet! Limousines were waiting to take everybody to the Prince of Wales Hotel. ‘We had negotiated the rates to death, but it worked and the guys were amazed! It wasn’t the kind of consideration they would get in the States’ says Karakos amused, never short of crisp details. All night long they would be signing contracts – sometimes painfully. Joseph Jarman of the Art Ensemble of Chicago even pulled out his knife saying ‘that’s my lawyer!’. Archie Shepp would hold onto some bitterness all his life, feeling cheated…Most of this ‘new thing’ (i.e. free jazz) would be recorded during August. Some would stay in Paris, such as the Art Ensemble, Alan Silva, and Archie Shepp, appearing again…

Many of them made one, sometimes several, recordings under their own names, all of them taking part in numerous sessions which took place at the Saravah studios, on Passage des Abbesses, then – when space ran out – at the Davout studios, in Porte de Bagnolet. Archie Shepp would create a few magic records – Yasmina, A Black Woman, and Blasé with the eternal Jeanne Lee…but this wasn’t the only landmark moment in this series.

One session followed another with intensity. In dark glasses and suffering from many sleepless nights, everyone was all over the place. The feeling of a state of emergency emerged, with tempo in turmoil. At the beginning of October the records dropped. With their multi-coloured cover and double gatefold, they perfectly illustrated the ambitions of the label: ‘To put the latest contemporary jazz back in the spotlight of pop culture.’ Almost immediately, Melody Maker devoted a full page to the story. For years later the shock waves would resonate in the rock scene – Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth never hid his references, just like the label Numero Group, from Chicago. No doubt about it, the free jazz agitators of the BYG Actuel series have long since become music legends. And though these firebrands set fire to the Paris underground, they always maintained an echo of the sacred fire that had fuelled the Pan-African Festival in Algiers

Discover other articles in our series, Crazy Jazzmen of Africa by Jacques Denis.

Follow Jacques Denis on Twitter.